How not to get Value for Money

The scoring mechanism which ruins your evaluation

When I started my career, Value for Money was what it said on the tin. You scored quality, calculated price and divided one by another. If something was 10% better and 10% more expensive than another offer, both bids scored the same. If something was 10% less expensive but the same quality, it won. Simples.

But too simple for a new breed of procurement professionals. “Hang on”, they said, “10% could be a lot of money and maybe we don’t want 10% better quality”. Ignoring simpler solutions, like setting quality minimums and just evaluating on price, they set about creating a new set of price evaluation measures which were labyrinthine in their complexity, the most insidious of which looks like this:

100% - (YourPrice-LowestPrice)/(HighestPrice-LowestPrice) x PriceWeighting

The result of this is usually to massively amplify otherwise small differences in price. Especially in procurements where the market is already competitive and the specification is clear. In these markets, it’s not unusual to see very tight ranges of bid prices.

Let’s say that there are two bidders and their prices are only 5% apart. The buyer uses a relatively normal price weighting of 40%. In this case, the bidder who managed to squeeze costs by 5% starts the rest of the competition 40% ahead of the other bidder. That low bid can score only 20% out of 60% on quality and still match a bid which scores full marks for quality. This doesn’t do the buyer any favours.

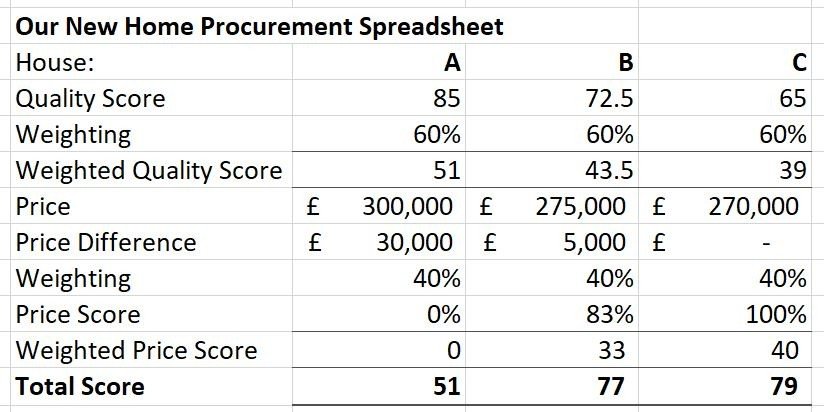

Let’s imagine another scenario. You’re buying a house. You and your partner are procurement groupies and decide you should set up a spreadsheet and make your decision on that. Don’t laugh, this is how my friends and I decide where we are going on holiday, but that’s another story. Spreadsheets are good things. Anyway, you both think House A is the best. It’s not perfect, but it’s pretty good. You give it 85 points our of 100. Your partner likes House C but you don’t. They score House C at 80 and you score it at 50. You average this for a score of 65. House B is “ish”. You both give it 72.5. Already we see that people rarely score anything below 50%, which is another way procurement undervalues quality. We usually only use half the available range. Anyway, you run the numbers and find the following:

Sample Scoring

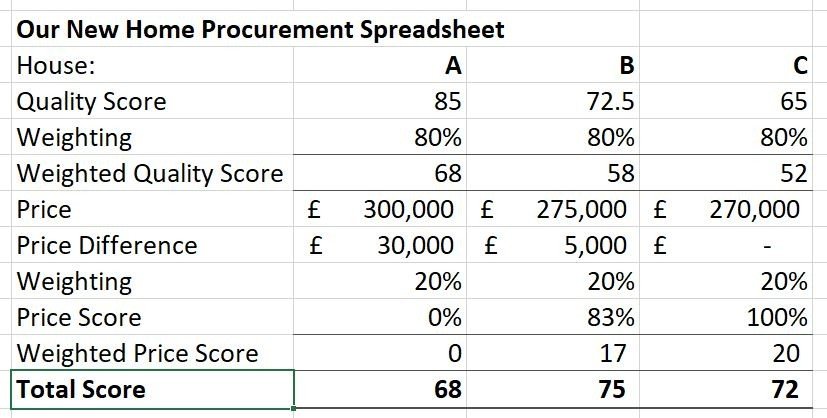

Your partner is ok with it. They preferred A but, for them, C is 10% cheaper and 5% worse so it’s a good enough choice. You are not pleased though. How can C score 28 points ahead of the house you both love, A, when A is only 10-11% more expensive? Must be the weightings. After all, this is the house you are going to live in for the next ten years. Price isn’t everything. So you convince your partner to run it again with a measly 20% weighting on price.

Sample Scoring with 20% price weighting

Huh. Odd. Neither of you really liked B much. Fortunately, your grandfather comes in and asks what the matter is. He explains that when he used to buy potatoes for the navy, they didn’t have computers and so instead, they just gave a score for potato quality and divided it by the price. They used to call it value for money. It sounds very old fashioned, but to humour him, you whip out a calculator and do it anyway.

Dividing quality by price results

Huh. Feels right. But it’s not what the spreadsheet said - so you shake your heads and buy House B.